Liah: Chess Tactics

Every beginner starts chess with one question in mind: HOW can I get better? Well, the answer is surprisingly simple.

BY LIAH IGEL

THE BRONX HIGH SCHOOL OF SCIENCE

HER LEAGUE COACH & HER NEWS COLUMNIST

Every beginner starts chess with one question in mind: HOW can I get better? Well, the answer is surprisingly simple. Anyone can get better at chess with the more time and effort they dedicate into practicing. One of the most common ways of doing so is through puzzles. In this article, I’ll cover some puzzles that I personally think every chess player should analyze and know about, as well as some that a professional master I interviewed recommends to analyze.

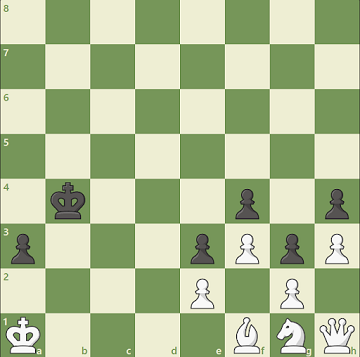

1. Material Disadvantage

As players start exploring and becoming more familiar with various concepts in chess, they are often taught that having more pieces means you are winning, with no exceptions. This is extremely misleading, and can discourage players from putting effort into winning once they get into a material disadvantage. In the position shown above, it’s clear that black is down in material. White is lacking not only a bishop and a knight, but also an entire queen, which surely makes it seem to be a fully losing position. In reality, the position is the exact opposite. After 1. .. Kb3 2. Kb1, a2+ 3. Ka1, Ka3, white is put into a semi-stalemate, and is forced to use his last available move, Qh2. After capturing white’s queen, black is able to promote to a queen and essentially reaches victory. I find this puzzle particularly meaningful, as it truly shows that not all “unspoken” rules are true, and one can still surely win even while suffering a supposed disadvantage.

2. Shortest Grandmaster Game

This is one of my personal favorite chess games, as it’s the shortest game played in real life between two professional grandmasters (Lazard vs. Gibaud). It lasts a total of only 4 moves, but still is full of surprises. After 1. d4, Nf6 2. Nd2, e5 3. Dxe5, Ng4 4. h3, Ne3, white is obliterated with only two options, each of which leaves him in either checkmate or a challenging situation. If white takes the knight with his f2 pawn, black will go Qh4, which soon leads to checkmate after g3 and Qxg3. On the other hand, if white doesn’t take the knight, his queen will be taken on the next move.

I think this game sends an amazingly positive message regarding ratings in chess: to an extent, ratings hold no real value and can genuinely mean anything. Despite the grandmasters’ high rankings, they had a quick and rather sudden game where many inaccuracies were made. We all know that this could very similarly happen in a game between two beginners, two intermediates, or any two-rated players. It’s important to try to not let the rating of your opponent intimidate you, as at the end of the day, both sides have an equal opportunity of winning.

3. Paul Morphy’s Amazing Opera Game

One of the most amazing and famous games in the world, the Opera Game, is considered to be the legendary Paul Morphy’s best chess match. In this position, Paul Murphy sacrifices almost all of his pieces in order to checkmate the opposition's king with just a bishop and a rook. I’d suggest looking through it move by move, and taking some time to analyze it on your own. At the very least, take a quick glance through this analysis chess.com provides, which you can find if you click here.

4. Impossible Pawn Hunt!

This position is trickier than the previous ones, but feel free to try to solve it on your own before scrolling down for the explanation. White to move!

When first observing the position, white seems to be in a sticky situation. It appears that the white king has no chance to reach the black pawn or even promote his own pawn on time. While it looks like a definite loss, white actually finds a way to produce a draw anyways. After 1. Kg7 h4, 2.Kf6 black has two options: to continue pushing his pawn, or to try to stop white’s advanced one. In the variation where black pushes his pawn, the position turns into a queen vs queen endgame (a draw) after 2. … h3, 3. Ke7, h2 4.c2 Kb7 5.Kd8, h1=Q, 6.c8=Q+. In the other variation, black has to move his king and go 2. Kb6, 3. Kf5, Kxc6, 4. Kg4, where white will go on to take the pawn, hence leading to a draw due to insufficient material. Both of these lines inevitably leave the perplexing position in a draw, despite all odds. I find this an extremely inspiring tactic, as even though it looked fully impossible, all in all there was a way. It goes to show that in your games this can always be the case; even if you may be struggling to find a solution, there may be one anyway!

You may be asking, what types of puzzles should I do? How do I know if I’m practicing the right skills? As a coach, I constantly encounter such questions with aspiring chess players. My answer is always the same: It’s important to base the difficulty and concepts of puzzles on the mistakes you make while playing games. After analyzing your games, note the mistakes you made and what commonly caused such blunders. Then, using your preferred chess website, you can set the topic of your puzzles to one of countless settings provided. These specific puzzles allow you to receive and practice puzzles on a particular skill, such as mate-in-1’s, blunders, forks, pins, and more. All in all, spending more time practicing and improving upon your mistakes using useful resources, such as puzzles, is extremely beneficial and will help players of all ratings improve!